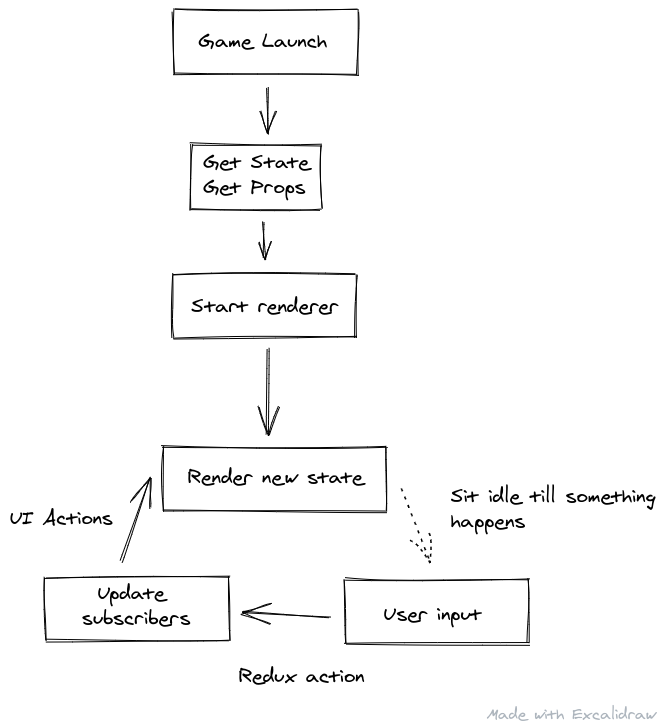

An architecture for Phaser JS + Redux

I've built a few games now with Phaser, and I think I've found a generally good mental groove for writing easily tested TypeScript games. In rough, user inputs trigger redux actions, which updates state, and optionally triggering UI Updates from the game renderer.

Goals

Oddly enough, for some of the games I'm making I want to avoid tying too closely to the game engine. There's a non-zero possibility that it will need to render the same game but in more than just a canvas ( e.g. a static svg) and so I want to keep as much logic in 'plain old JS' - this disconnect of 'game' from 'renderer' is not a foreign concept (games working with openGL vs DirectX comes to mind) but this introduces a really important seam for composition and testing.

Terminology

Game Props - The parts of the game's level setup which are constant. This ranges from game config (original version of the board, colour scheme, game mode settings etc)

Game State - The parts of the game which change (moves made, words found, tiles removed, user selection states)

Renderer - A way to display the current props + state, y'know, the game bit

Redux - A state management library which constrains the set of places the games state can change into a single place. Renderers can subscribe to know when changes have been made.

Redux Store - A five euro name for a 10 cents idea, it's just the name of the db for the JSON and the API for subscriptions

Redux Actions - It is the renderer's responsibility to tell the game engine that the state should change, this is done by sending redux actions into the games state. An action is basically a message sent to the store.

Overview

Setup

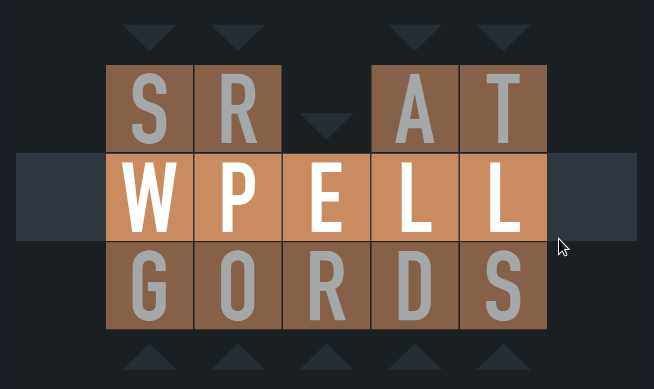

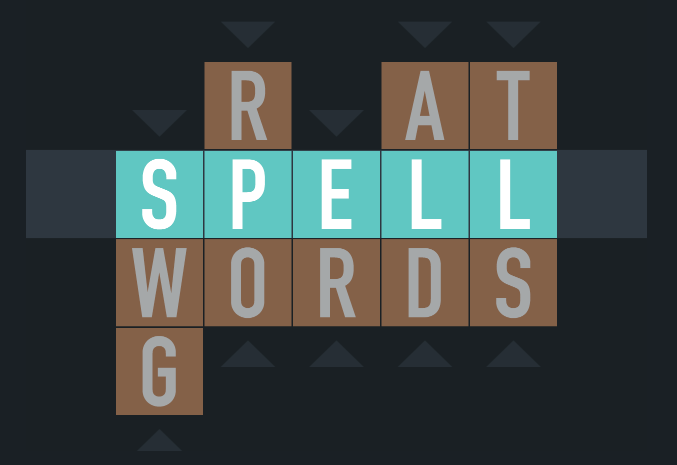

Let's take a game of Typeshift as an example. That link will let you play the game too BTW.

We'd need to start by having Props which look something like:

ts

Then, because we know as you go through the game finding words and selecting letters, we'll need some sort of way to describe the changes from the original baseline, where here I moved the first column down by one:

We'll mix those props in with the changing settings:

ts

So, to start up the game we'd need a way to grab or generate the props and state. Then this can be put into the Redux store. Once the store is ready, then you can create a renderer.

As we're talking about Phaser, that means making a Phaser Scene which subscribes to the Redux store.

ts

This is pretty vanilla, all Phaser games would end up with something like this. The only specifics are that it delegates grabbing props and state to a host object which could be anything (e.g. maybe there's a Daily host which gives the same props every day and uses localstorage for state)

Next let's look at the TypeshiftScene, it's a Phaser Scene subclass which encapsulates creating the UI, and keeps references to all those objects. Here they are encapsulated in Column objects. The key to think about is launching the game, setting up input and then subscribing to upcoming state changes.

ts

Waiting for Input

So, from that original diagram, we're now at the "waiting for input phase". The game doesn't do anything at this point unless the user specifically does something. Let's look at registerKeyboardInput as that is the simplest input function. This function uses the Phaser API for keyboard input to listen to browser events and then will convert those into actions in the Redux store.

ts

Update State

Lets follow what happens when up is called, first to give you a sense of how the actions connect to the store, up is created in the same place as the Redux store.

ts

This setup means when code like this is called:

ts

It becomes the responsibility of moveColumns to edit the app's state, and to let the renderer know what sort of changes it should make to the UI:

ts

When this function is finished, the store of the app is updated with the new state and any parts of the app which are set to listen to the store (our TypeshiftSceneClass did this via this.state.store.subscribe) will start their update cycle.

UIUpdates

Now, in a React codebase we have the virtual DOM and the React reconciler. The reconciler's job is to look at the current state of the DOM and the virtual DOM and handle the transformation from where it was to where it should be. I could try build a Phaser VDOM reconciler (it has been explored) but the UIUpdates is an acceptable hack to work around not having that tool.

So roughly, the UIUpdates is a way to scope "changes" to the Phaser DOM (Objects, Sprites, Text, Tiles etc) and handle all the state changes relating to a certain scope.

ts

In this case, the responsibility for this function is to dive into the game's 'internals' aka the exposed Phaser DOM on the class of the TypeshiftSceneGame and set the Y position of the columns according to the (now updated) state.

I spent some time thinking about whether uiactions should be async to handle chaining transitions for animations, and so far have not needed it. We'll see whether that holds.

Flow

So, let's try go over this one more time in short:

- Get props (unchanging per level) and state (things which change over time)

- We start up a redux store with both the props and state

- Create a renderer (phaser) which listens to changes in the store

- Set up the renderer based on the new state

- The renderer is responsible for setting up user-input

- User input eventually triggers a redux action to update the game's state

- The game state is updated inside the redux store via action functions

- If any of these state changes requires a UI change, then the state includes a list of UI updates

- Run any UI updates which make renderer changes

This might feel pretty abstract for small-ish games, but it allows for:

- It avoids a massive single Phaser Scene where state changes occurs from many places

- Many possible renderers sharing most of the code

- Many seams for writing tests without relying on very high level integration tests

- A pretty obvious structure for where for most code in a game can live

- Re-using existing redux tooling

This architecture is built for games which require user input for the next thing to happen, I don't think something like this would be a good fit for Flappy Royale for example (~100 birds realtime flapping through pipes concurrently ) where a runloop with scoped state is probably a better fit.

Related: You can see an example of how I use a text renderer for game state in [[tests/inline-snapshots]].

Yeah, but why Redux?

I didn't just create this architecture ahead of time by cleverly analyzing what I needed and got it right, it took writing two games where they both kept heading in this direction till eventually I started formalizing and backported the architecture to the projects.

In the last ~5 years, I've wrote quite a lot of React-ish code, and see a lot of value in the explicit narrowing of state changes through as tight a function as possible.

The first game had an explicit setState function on the Phaser Scene class which handled both state updates and ui updates. This was mixed with a multi-cast delegate pattern which allowed for many subscribers to know that the state had changed. I used this to allow for things like analytics, host callbacks and dev tooling.

This pattern worked pretty well though it started to hit issues when the number of responsibilities started to grow in that setState function, trying to keep it readable and focused meant moving a lot of useful internals out into sub-functions which often meant breaking the OOP contracts in those functions.

So I knew that a home-grown state mangement system was doable, but maybe I should formalize. I spent a day auditing the state of different state management systems by making quick apps and trying to deep dive in to their docs. The contenders were MobX, Vuex, Redux, Recoil and Jotai.

In part, it was made much easier because a few of these are strongly tied to a UI library to the point where they can't be used without it ( Recoil, Vuex and Jotai ) which really only left MobX vs Redux. I have a bit of an aversion to reactive programming after building a non-trivial iOS app in RX, but I was open to at least seeing what was going on.

After trying both, I concluded that there's a lot of MobX's value which I would not use. I expected to mostly have a pretty small state object, but I could see that from the current architecture I could drop the UIActions abstraction in favour of having a renderer listen to changes in the state tree.

What went against MobX was the feeling that introducing reactive programming in one aspect of an app has a tendency to leak into all parts eventually, and I'm wary of that.

Redux won me over by being very small and extremely well documented. The core dependency was enough to get started but very quickly I realized I was re-creating the Redux Toolkit and I should just lift my abstraction to that. Things I like:

- These sections of the docs: "Thinking in Redux", "Redux Essentials", "Style Guide"

- The TypeScript support after switching to Redux Toolkit was very tight

- Redux Toolkit uses immer to force immutablility

- Redux Devtools is way better than my version

- Massive community, got answers in Discord almost instantly

Like all tools, you can get very complicated with your usage of Redux - but that's usually the cost of doing complex things. I think in these games I'm getting enough value to pay for it's abstraction costs and raw additions in kb. Aside from a deterministic random number generator, this is the only dependency I use outside of the renderer Phaser/svg.js.